This step in our ongoing series exploring the Far Eastern lands of Warhammer, is a bit of a departure, as it's not really about any form of Warhammer at all. What it is about is Nippon TVs 1978 adaptation of Wu Ch'eng-en great Chinese story Monkey one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese Literature.

Sha Wujing or Sandy as he is known in the TV series. Here's a quick sketch of Sandy, I've added a backpack, pouch and gourd to make him look a little more like a typical overburdened Dungeons & Dragons adventurer.

|

| Sha Wujing / Sandy Rough Sketch [ZHU]18 |

It should be clear that Sandy is a monster, a cannibal, who nontheless becomes a hero in the story by trying to overcome his monstrous nature, as is true of the other pilgrims - Monkey, Pigsy and Tripitaka (although his monstrous adherence to principle over practicality, is not so easy to discern). It is also easily observed that most of the demon-monster-spirits that Tripitaka and his entourage encounter are aspects of human nature exaggerated to monstrous, demonic form, but who nonetheless, are all souls on the path of Karma heading towards enlightenment. The lazily simplistic 'good vs. evil' or 'us-vs-them' tropes found in modern western fantasy depictions of monsters such as Orcs and Chaos Ratmen as Other (often based on historical cultural racism and bigotry) in media are quite absent, and there is something to be learned there, not only in dealing with some of the more problematic ideas in Western Fantasy, but also in structuring an approach to Oriental Adventures that doesn't simply reproduce the tropes of Western Fantasy in Oriental drag.

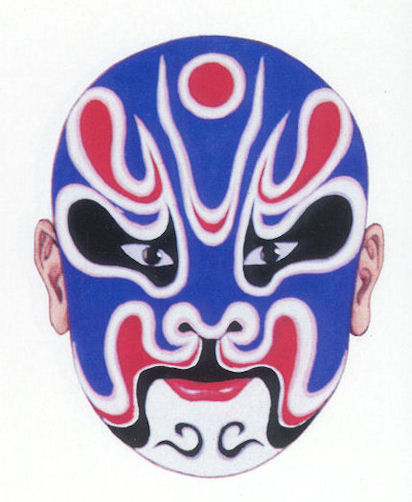

Anyway, let's have a look at how Sha Wujing is traditionally portrayed:

| Sha Wujing | Bejing Opera |

|

| Sha Wujing | Beijing Opera Mask |

|

| Sha Wujing | Bejing Opera Maks | Cigarette Card |

|

| Sha Wujing in Xiyou yuanzhi (西遊原旨) 1819. |

|

| Sha Wujing | Sandy | Shiro Kishibe |

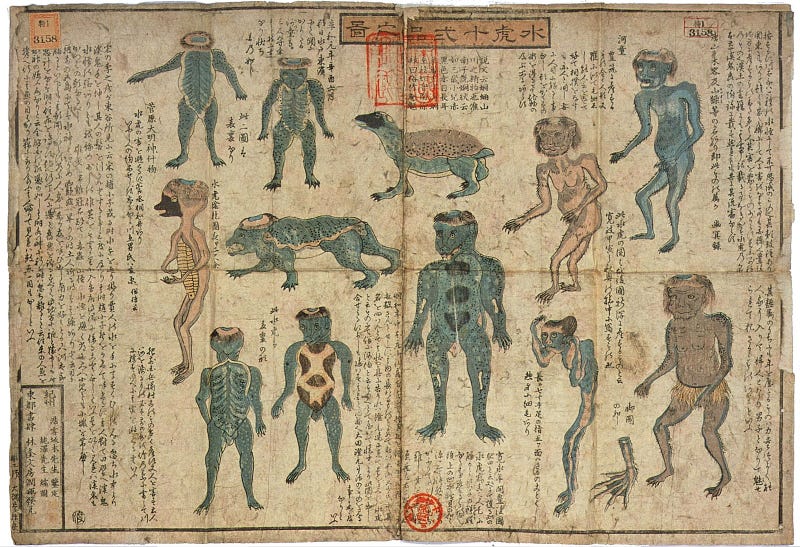

Well, I think the answer appears to be in the Japanese Oni known as Kappa.

|

| Japanese Kappa with a cucumber |

|

| Kappa from Gazu Hyakki Yagyō ("The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons") by Toriyama Sekien |

|

| Kappa Kappa |

These mysterious and strange turtle-people are, like Sandy, canibalistic water creatures.

- the over-all dark green colour,

- the fringe creating a visual 'beak'

- bald head, which is covered with a dish-hat

Kappas head-bowl must contain water, and if it dries out they die. In the TV series Monkey very often the four Pilgrims run out of water, and Sandy, rather than drinking it, takes his bowl-hat off and splashes it on his bald pate, much to the comedic annoyance of his brethren.

Kappa are known to lead horses to drown, indeed one of the many names of the Kappa is Komahiki or "steed-puller". If so, this is played up as something of a joke in Monkey - Sandy is most often the one seen leading Horse by the reigns - who is herself (or himself, in the second series of Monkey ) is actually a water-dragon, a river-spirit transformed into a Horse.

Kappa pull ones shiridama (or bum-ball, an imaginary internal organ) out of peoples bum-holes. This doesn't seem to have influenced Sandy, but maybe there are some bum jokes I missed. Also, on the subject, Arthur Waley's abridged translation of Wu Cheng'ens Monkey, does contain much of the crude, frenetic energy and boisterous humour of Monkey, it's a folk-tale infused with humour culture and philosophy, not a dry studious work. Unfortunately Sandy isn't in it much, which probably suits him quite well.

|

| Sandy | Jamie Hewlett |

And we can also see below a illustration of George Washington fighting the British by Utagawa Yoshitora. While George himself is rendered as a Japanese gentleman with 19th Century western clothing and armaments, probably the most striking element is that the British are dark skinned. Perhaps based on the illustrator hearing some anecdotes of Black British fighting in the American Civil War on the English side, but more likely to represent the British as Oni - a mythological rendering of that signifies sympathy with Washingtons cause than his adversaries. Putting aside the problematic Japano-African racism that gets thrown here, a mainly folk-mythological reading is supported not only by the large number of mythological and folkloric figures - dragons, giant eagles, that Washington fights off - but also apparently by the British Officer being named Asura - the sanskrit name for the buddhist-hindu kind of stubborn wicked demon-monster-spirits who will not change their ways...

|

George Washington fighting the British | Utagawa Yoshitora | 1861| via |

Interesting article. Thanks for writing it. For some reason I found the George Washington graphic very striking. I struggle to describe it, but it feels like a sort of reverse cultural appropriation (which isn't the correct term but the closest thing I can grab right now). Very cool to see the themes that emerge from other cultural groups when describing a well known story from your own.

ReplyDeleteGlad you liked the piece, you've given me some things to think about as well, so thank you for your comment.

DeleteThat George Washington illustration is great, and only turned up relatively late in writing this piece, but seemed to underpin a lot of of what is going on. It brings a certain freshness, seeing something seemingly familiar portrayed in a different way, a kind of anti-recuperation, a reawakening perhaps.

Agree 'cultural appropriation' isn't apt, it's unfortunate that the phrase is so readily available, as it frames any kind of cross-cultural influence or sharing within a hierarchy of power and erasure that is not always present or meaningful. Clearly the processes of assimilating the (american) narrative into the dominant culture (japan) are there - the idea that 19th C. japanese were a colonial power robbing white americans of their culture is ludicrous, although the erasure of white American and British voices and the constuction of a (clearly) holographic, fantastical West.

I used the phrase 'cultural interchange' above, perhaps something more along the lines of 'cultural osmosis' (although that tends towards an individuals acculturation) or 'cultural exchange' (although that tends towards visiting cultures for educational purposes) or 'cultural dialogue' (although this, like 'cultural appropriation' posits cultures as static things, rather than dynamic ones). Hmm...

Interesting that you'd focus on Sandy. I thought you might prefer to write about one of the others. ;)

ReplyDeleteThe Japanese seem to love Journey to the West; as well as Monkey, there are endless films and TV shows, and then the multimedia juggernaut that is Dragonball although it's deviated from the original a fair bit as it's gone on. I can't think of another example of one culture fixating on a part of another's mythology in such a way; maybe the way the French took on and expanded the King Arthur mythos?

I've also found it fascinating how Monkey is such a cornerstone of British culture for a certain generation, despite being a Japanese import of a Chinese import. It says something about the power of the story, I suppose.

Ha, yes, I'm nost sure where Furui Hanma is heading, but it's possible each of the pilgrims will get their own side-trek. If you dig around on the blog you'll see there are a few posts about certain porcine fantasy creatures.

ReplyDeleteI'd always assumed Dragonball's relationship to Journey to the West was a bit like Marvel's Thor compared to the Norse Myths, but its outside my frame of reference.

Yes, Monkey is as British as Balti and Punch and Judy. the wild lands of China no more strange or exotic as the New York of Spiderman or the Tunisian deserts of Tatooine. Definitely, the power of stories (and thir reflections of human nature) do play a part, but I also wonder if Sun Wukong wearing a cub-scouts yellow neckerchief also had something to do with it...